What is PAH?

What is PAH

What is PAH?

PAH is a rare and severe disease characterised by progressive narrowing of the pulmonary arteries. If left untreated, it eventually results in right heart failure and death.2,3 Knowing the signs and symptoms of PAH can help prolong your patient's life. Explore below to find out more.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) refers to elevated blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries and can be caused by various pulmonary and cardiac pathologies that increase pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP). PAH describes a subgroup of patients with PH characterised by the presence of pre-capillary PH, defined as mean PAP >20 mmHg, mean pulmonary arterial wedge pressure ≤15 mmHg and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) >2 Woods units, in the absence of other causes of PH. 4

The 2022 European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines categorise PH into 5 main groups, with PAH being group 1.4

Clinical classification of PH

Types: Idiopathic PAH, Heritable PAH, Drug induced PAH, Associated PAH

Prevalence: Rare

Treatment strategies:

- Medication

- Lung transplantation

Types: IpcPH, CpcPH

Prevalence: Very common

Treatment strategies:

- IpcPH: Treatment of LHD

- CpcPH: Treatment of LHD,

Potentially: PAH drugs (trials)

Types: non-severe PH, severe PH

Prevalence: Common

Treatment strategies:

- PH-lung disease: Optimized care of underlying lung disease

- Severe PH: Potentially: PAH drugs (trials)

Types: CTEPH, Other pulmonary obstructions

Prevalence: Rare

Treatment strategies:

- Surgical therapy: PEA

- Interventional: BPA

Types: hematological disorders, systemic disorders

Prevalence: Rare

Optimized treatment of underlying disease:

Potentially: PAH drugs (trials)

Clinical classification of PAH

Idiopathic PAH (IPAH)

IPAH is the most common form of PAH, accounting for approximately 50–60% of cases in Europe and the USA.4 It occurs sporadically without a family history or other identifiable risk factors.5

Heritable PAH (HPAH)

HPAH accounts for approximately 6% of PAH cases and includes patients with a family history of PAH and those carrying a mutation in a gene known to be associated with PAH.6

Drug and toxin-induced PAH

PAH can be associated with exposure to certain drugs or toxins, particularly appetite suppressants, such as aminorex, fenfluramine derivatives and benfluorex. These drugs have been confirmed to be risk factors for PAH and many have been withdrawn from the market.7 Since then, additional new drugs have been identified or suspected as potential risk factors for PAH, including bosutinib, sofosbuvir and leflunomide.8

Associated PAH

Many patients with PAH have an associated disease, such as connective tissue disease, congenital heart disease, portal hypertension, HIV infection or schistosomiasis.4

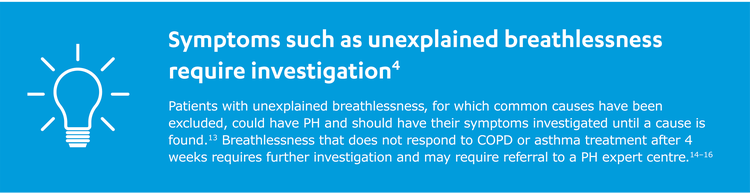

PAH affects the small vessels of the pulmonary circulation. Changes to the pulmonary vasculature lead to the typical symptoms of PAH. Symptoms, such as dyspnoea, are often non-specific and can be associated with a number of underlying conditions.10

These symptoms may be accompanied with a cough, sometimes with haemoptysis. Some patients may even develop hoarseness, caused by compression of a nerve in the chest by an enlarged pulmonary artery.4As PAH advances, patients can develop a bluish discolouration due to cyanosis. The continued strain on the heart can lead to swelling of the face, ankles, abdomen and feet due to oedema.4 Too often patients only present when they are no longer able to continue with daily activities. By this time, the disease may have progressed to a point where the patient is bedridden from shortness of breath or other symptoms.

Adapted from Humbert et al. 2022

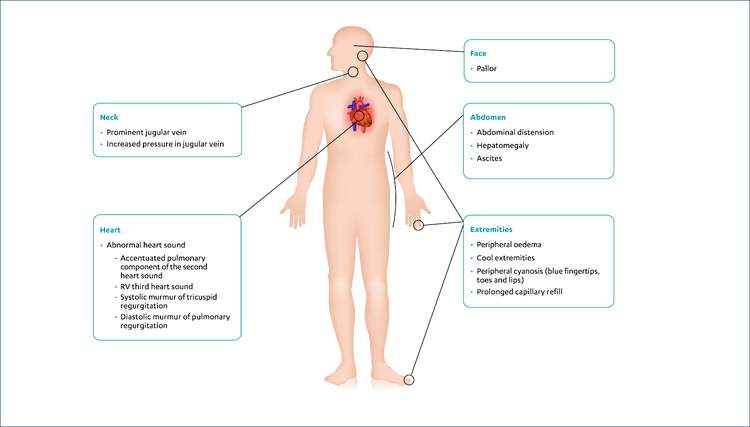

Clinical signs of PAH

Click to enlarge the image below to see all the clinical signs that point to PAH.

Adapted from Humbert et al. 2022

More signs to look out for, listed by cause4:

- Central, peripheral, or mixed cyanosis

- Accentuated pulmonary component of the second heart sound

- RV third heart sound

- Systolic murmur of tricuspid regurgitation

- Diastolic murmur of pulmonary regurgitation

- Distended and pulsating jugular veins

- Abdominal distension

- Hepatomegaly

- Ascites

- Peripheral oedema

- Digital clubbing: Cyanotic CHD, fibrotic lung disease, bronchiectasis, PVOD, or liver disease

- Differential clubbing/cyanosis: PDA/Eisenmenger’s syndrome

- Auscultatory findings (crackles or wheezing, murmurs): lung or heart disease

- Sequelae of DVT, venous insufficiency: CTEPH

- Telangiectasia: HHT or SSc

- Sclerodactyly, Raynaud’s phenomenon, digital ulceration, GORD: SSc

- Peripheral cyanosis (blue lips and tips)

- Dizziness

- Pallor

- Cool extremities

- Prolonged capillary refill

The increase in pulmonary arterial pressure (afterload) makes the right heart work harder, resulting in right ventricular hypertrophy, and leading to the typical symptoms of PAH.11 Initially, the heart is able to compensate for the increased pressure;12 however, as the disease progresses, the right ventricle (RV) becomes dilated, eventually resulting in a number of potential consequences:

- Right ventricular hypertrophy, which can, on occasion, reduce blood flow and lead to ischaemia of the right ventricle4,12

- Right heart failure, including all typical signs of systemic venous hypertension, whilst also occurring during a low cardiac output state. Syncope is a severe manifestation of right heart failure11

- Dyspnoea at progressively lower levels of exercise, eventually presenting at rest and often with frank syncope11,12

- Disability and death, occurring sooner if effective treatment plans are not initiated11

Read more about this in the Pathophysiology section.

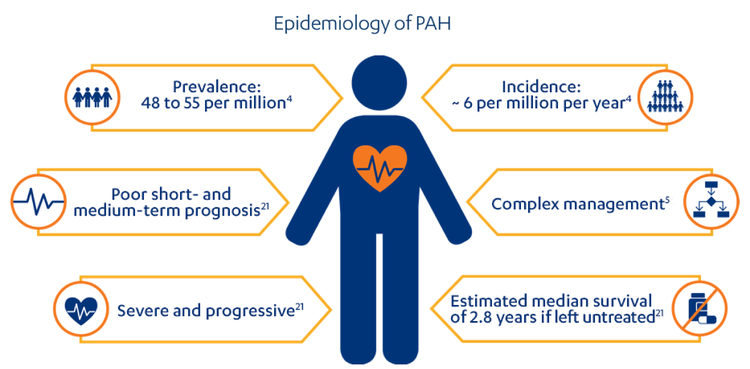

PAH is a rare, progressive disease.21 Without treatment, PAH carries a poor prognosis.22 The course of PAH is variable and the rate at which disease progression occurs depends on the type of PAH as well as several other factors, such as the underlying aetiology of the patient's disease, age, associated conditions and comorbidities.4,23 While there is currently no cure for the disease, modern PAH therapies can markedly improve a patient's symptoms and slow the rate of clinical deterioration.11

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension

Who is at risk?

A number of registries over the years have reported baseline characteristics and outcome data on >10,000 patients with PAH, providing important insights into the evolving epidemiology of PAH and facilitating the development of prognostic indicators for the disease.24

PAH aetiology

- PAH associated with congenital heart disease (CHD-PAH)5

- PAH associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc-PAH)

SSc patients are at high risk of developing PAH,25 which can be severe and fatal, and accounts for >50 deaths in these patients.26 - PAH associated with portopulmonary hypertension (PoPH-PAH)

Patients with PoPH-PAH have also been identified as a higher risk cohort compared with IPAH.27

Age and sex

PAH has been thought to predominantly affect younger individuals, mostly females;24,30 this is currently true for Heritable PAH, which affects twice as many females as males. However, recent data from the USA and Europe suggest that PAH is now frequently diagnosed in older patients (i.e. those aged ≥ 65 years, who often present with cardiovascular comorbidities, resulting in a more equal distribution between sexes).24

Though the exact causes behind the development of PAH remain unknown, research has led to a better understanding of the underlying pathophysiology. PAH is a complex, multifactorial condition involving numerous biochemical pathways and different cell types.2

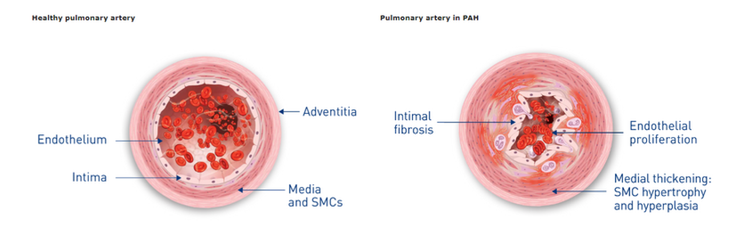

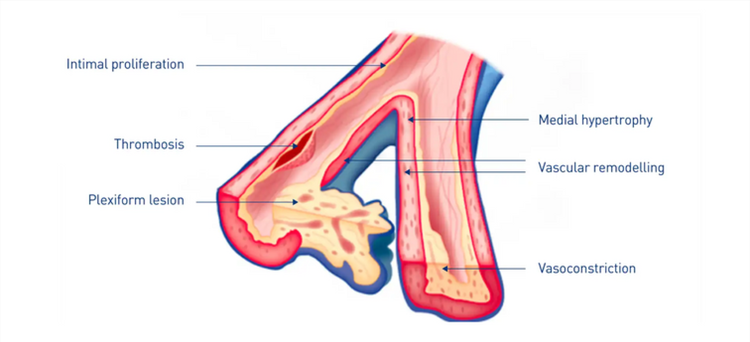

Narrowing of the pulmonary arteries occurs in PAH as a result of vascular remodelling, which involves changes to all three layers of the vessel wall via multiple pathological mechanisms.2Vascular remodelling leads to chronic elevation of PVR and PAP. This, in turn, leads to increased afterload on the right ventricle, eventually progressing to right heart failure.2,17

Vascular remodelling in PAH

Adapted from Gaine et al. 20102

Histopathological features

The prominent pathological features of PAH include:2,18,19

- Intimal proliferation and medial hypertrophy

- Remodelling/fibrosis of the adventitia

- Development of plexiform lesions at arterial branch points

Adapted from Gaine et al. 200018

Ventricular disfunction

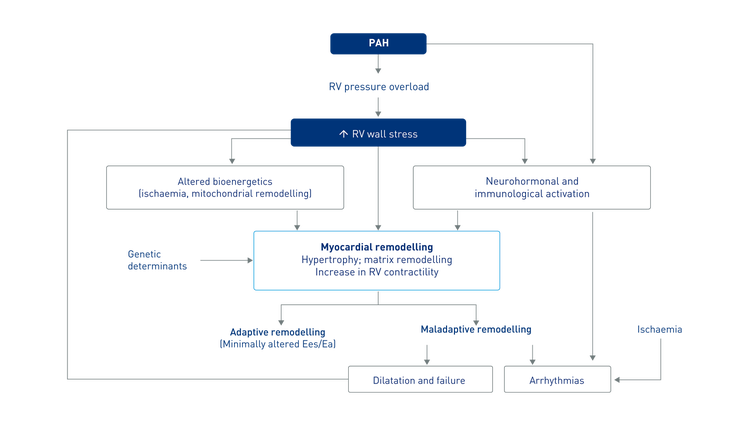

The increase in PAP (afterload) strains the right side of the heart. Initially, the right ventricle can compensate for the increased afterload by undergoing remodelling, including increased contractility, hypertrophy and dilatation. As PAH progresses, however, the heart can no longer compensate and becomes uncoupled from its load.17,20

Adapted from Vonk Noordegraaf et al. 201329

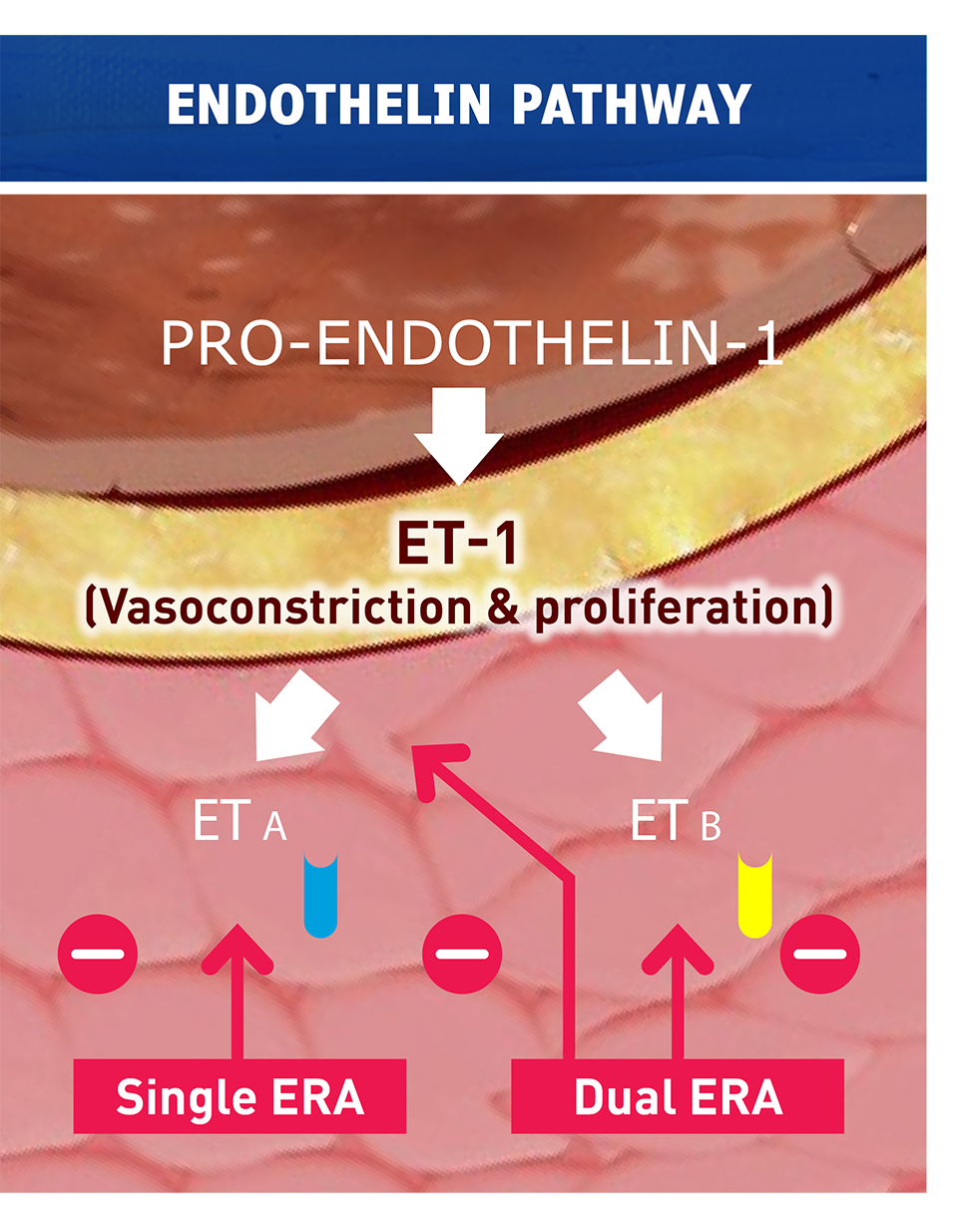

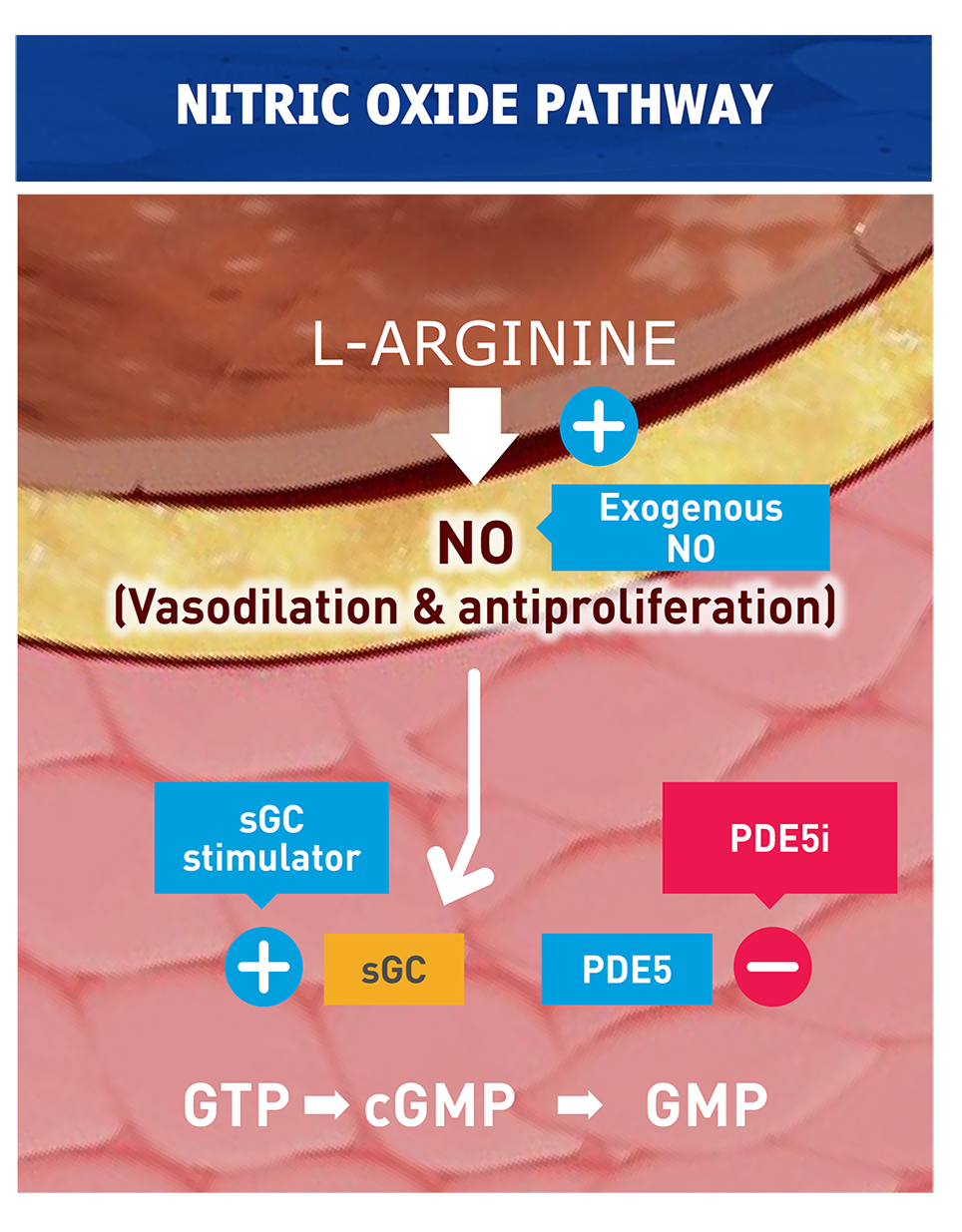

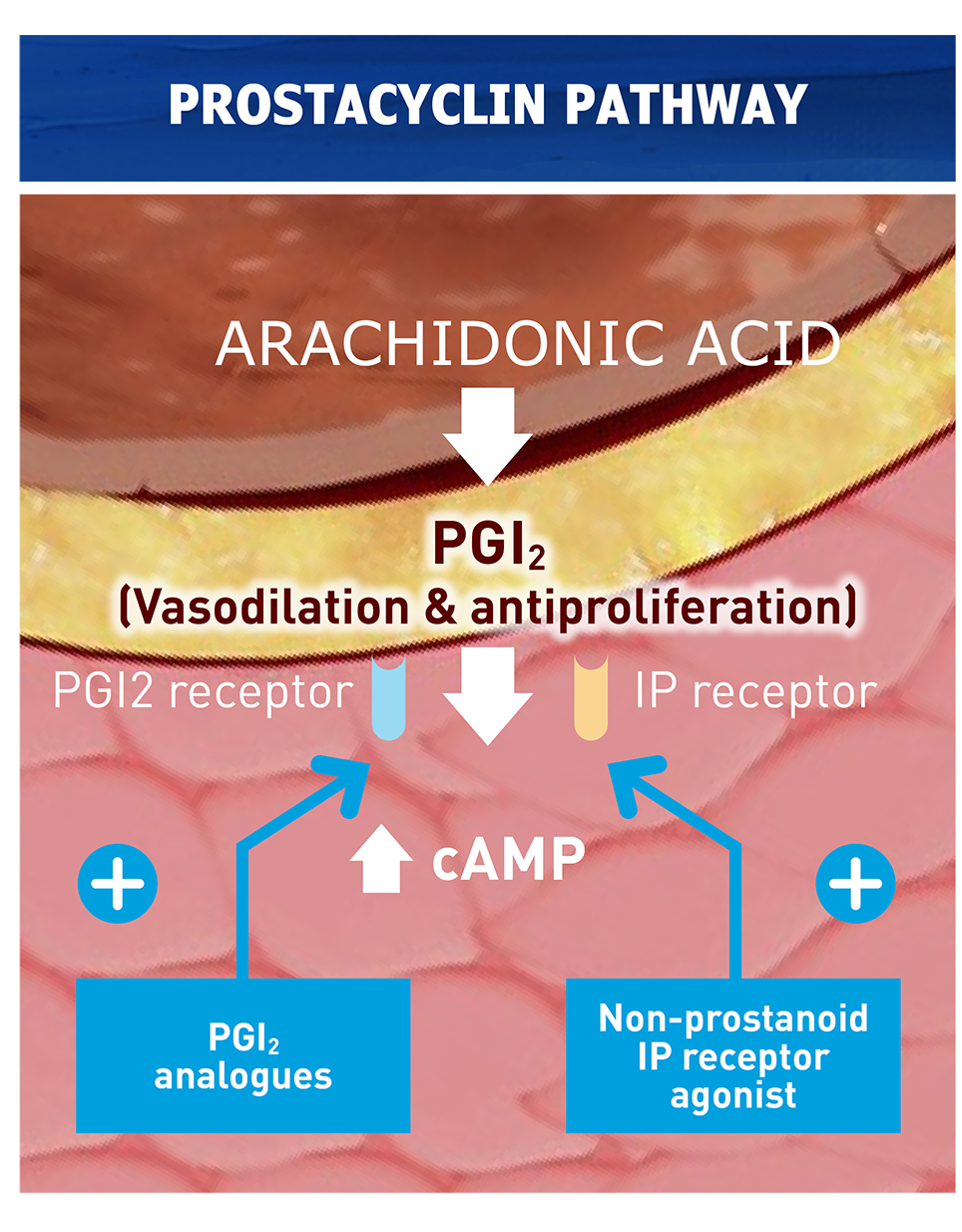

Hormonal pathways

Several hormonal processes are involved in the pathogenesis of PAH. Each of these are targeted by different, currently approved therapies.4

Adapted from Humbert et al. 2022

Continue reading

Find out about the different strategies that can help you diagnose PAH in a timely manner.

Patients with suspected PAH should be referred to a PH Center for further investigation and treatment.

We're here to help.

Would you like to know more about the screening and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension? Book an appointment with a Janssen product specialist by clicking the button below.

IpcPH: Isolated post-capillary Pulmonary Hypertension; CpcPH: Combined post-capillary Pulmonary Hypertension; PEA: pulmonary endarterectomy; BPA: balloon pulmonary angioplasty; HHT: hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia; Ea: arterial elastance; Ees: end-systolic elastance

Do you have a question for us or did you not find what you were looking for? Let us know and one of our Janssen's specialists will contact you as soon as possible.

Discover here the Janssen's portfolio and product SmPC's.

On this page you will find interactive 3D animations of the human anatomy and various syndromes. This allows you to zoom in on the anatomy, tissue structures, disease mechanisms and the course of the disease.

References

- Lau EMT et al. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015; 12(3):143–155.

- Galie N et al. Eur Heart J 2010; 31(17):2080–2086.

- National Health Service (NHS). Pulmonary hypertension overview. 2020. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pulmonary-hypertension (last accessed February 2023).

- Humbert M et al. Eur Heart J 2022; 43(38):3618–3731.

- Galie N et al. Eur Heart J 2016; 37(1):67–119.

- Ma L, Chung WK. J Pathol 2017; 241(2):273–280.

- Montani D et al. Eur Respir Rev 2013; 22(129):244–250.

- Simonneau G et al. Eur Respir J 2019; 53(1):1801913.

- Bossone E et al. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013;26(1):1–14.

- Humbert M et al. Eur Respir Rev 2012; 21:306–312.

- Montani D et al. Orphanet Rare J Dis 2013;8:97.10316.

- McLaughlin VV et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1573–61.

- Karnani NG et al. Am Fam Physician 2005;71:1529–37.

- Ferry OR et al. J Thorac Dis 2019;11(Suppl 17):S2117–28.

- Yang IA et al. COPD-X Concise Guide, 2019.

- National Asthma Council. Australian Asthma Handbook v2.1, September 2020.

- Vonk Noordegraaf A et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(2):236–243.

- Gaine S. JAMA 2000; 284(24):3160–3168.

- Jonigk D et al. Am J Pathol 2011; 179(1):167–179.

- Vonk Noordegraaf A et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62(Suppl 25):D22–33.

- D’Alonzo GE et al. Ann Intern Med 1991; 115:343–349.

- Hoeper MM et al. Int J Cardiol 2016; 203:612–613.

- Barst R et al. Chest 2013; 144:160–168.

- Lau E et al. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017; 14:603–614.

- Rhee RL et al. Am J Respir Crit Care 2015; 192:1111–1117.

- Kolstad KD et al. Chest 2018; 154:862–871.

- McGoon MD, Miller DP. Eur Respir Rev 2012; 21:8–18.

- Hoeper MM, Gibbs JSR. Eur Respir Rev 2014; 23:450–457.

- Health and Social Care Information Centre. National Audit of Pulmonary Hypertension, 2013. Available at: https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub13xxx/pub13318/nati-pu... last accessed May 2020).

- Montani 2020: Montani D, Girerd B, Jais X, Laveneziana P, Lau EMT, Bouchachi A, et al. Screening for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults carrying a BMPR2 mutation. The Eur Respir J 2020;58:2004229.